Maybe you no longer find playing your sport as fulfilling as it used to be. You think if you stopped playing altogether you would be better off. Perhaps you are feeling a bit slower, a bit older and wonder if it's time to hang up your cleats. Maybe you have been injured and are considering your return to play with some trepidation. You may think perhaps you should just stay away. There are myriad situations which may prompt an athlete to ask the ultimate question. The decision to stop playing your sport is a big one, and can be quite daunting to consider. You are fortunate that you have the option; many athletes have the proverbial rug pulled out from under them through career-ending injury or forced retirement as they are replaced by younger talent. It's never easy, but there are some questions you can ask yourself that might help to put everything in perspective. Once you can see more objectively, the decision to make will become clearer. Of course as an athlete the word "quit" is not in your lexicon. In making your decision, you need to understand "quit" is not what you are doing. If through much soul-searching and rational thought you decide to leave your sport, rest assured you are not "quitting." You are making a mature, informed decision that is best for you. Your responses to these questions should reveal your beliefs about yourself, your sport, and what is truly in your heart, head and gut on this matter. In typical Socratic fashion, follow-up questions will challenge those beliefs. What emerges is valuable dialogue that gets to the true heart of the matter. So what questions should you ask yourself to get started? Try these:

If injury prompted your decision-making, ask yourself:

Many of the issues or feelings you may be experiencing don't have to result in a black and white decision. Burnout, fear or anxiety, lack of confidence, all have a very real impact on how we feel about playing. But they can also be overcome using mental tools and focused effort on your part. A sport psychology consultant, for example, can teach you how to use these tools to help you regain confidence, to love the game again and to get back whatever it is you think you may have lost. The decision to stop playing, in most cases, is and should be yours alone. Sometimes talking it out with others can be helpful. Parents, family, coaches and friends are all great people to bounce your thoughts off of. Just be sure to take into consideration that the closer they are to you and the situation the more difficult it may be for them to step back from their own biases and perspective. Ultimately, though, your support system should want you to do what is best for you. If you choose to seek assistance, a professional can guide you through the questioning process and help you to put everything in perspective through an objective lens. So ask yourself the tough questions, see how you feel when you consider alternatives to sport, talk with others and seek professional support if you wish. And keep in mind that no decision is necessarily set in stone. What is right for you now might change in the future, and maybe you will decide to go in the other direction later. Just remember it's up to you.

0 Comments

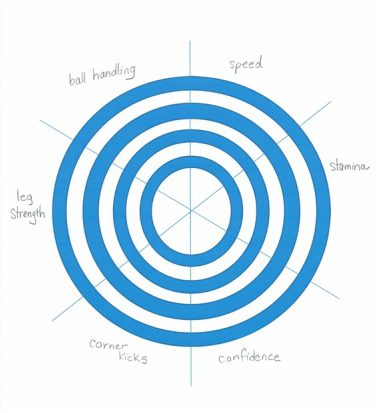

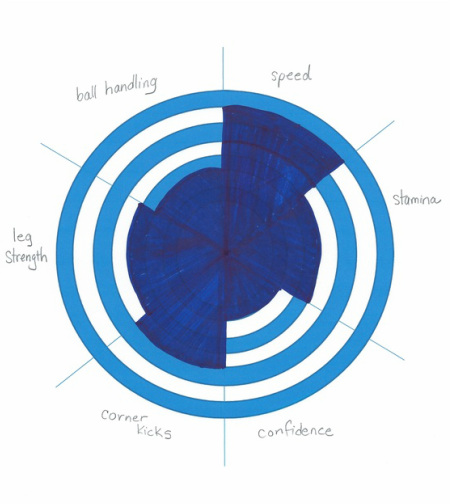

As an athlete, you have probably heard a lot about the importance of setting goals for motivation and continued success. There are guidelines for setting goals (see Staying Motivated: The Principles of Goal Setting) which are pretty straightforward. What can be difficult, though, is deciding what skill areas or behaviors should be the targets of goals you set. Do you need to set a goal to learn to hold the bat if you have no difficulty doing so? A simple tool to help you define what areas you may need to improve is a target board. Draw a target on a piece of paper, with at least 5-7 concentric circles. Next, consider behaviors, skills and attributes necessary for success in your sport. These should be general and objective, not specific to you (yet). What do you think an elite athlete in your sport would have, as far as skills, behaviors and physical attributes? For example, consider a soccer player, and what he or she might list:

Now look at your own list and circle the items you feel you could improve upon in your game. If you circle six items, divide your target into six sections like pie pieces. Seven items, seven sections, and so on. Label each section. Next, using the bullseye as the "elite" level, rate yourself on each item, counting back ring by ring until you get to where you feel you currently fall on that scale. With the bullseye as perfect, the further from the bullseye you are, the more you need to work on this area. Put a mark there. When you have done this for each item, color in the sections from your mark to the bullseye. When you have finished, you will have a visual representation of skills and behaviors you feel you need to work on, and where you may need to apply more or less effort to setting goals. This visual method is very effective for creating your mindset to attain goals you seek. You may also find that you have actually been focusing on areas in the past where you really are already better skilled. You can now use more effective time management, be more focused with your efforts in training. Your training will be more effective and productive overall.

Be sure to take the next step, actually setting goals in each area so you can achieve the "bullseye" all around. Follow up after a certain time (6 weeks, 3 months, whatever you set as your timetable), and re-do the target with your new assessment rankings. Make sure you are progressing each time. It might be helpful to have a teammate or coach help with the whole assessment process as well, either from the beginning, or once you do your reassessment, for a second opinion and support as you work toward your goals. If you are not making progress, you may need to look at the specific goals you created for each area, and make sure that the steps you envisioned needing to take to reach the goal really will take you where you want to go. Remember, the target areas are general, based on your idea of an elite player. Your goals, once you set them, will be much more specific. By meeting your specific goals, you will form a better mental picture, mental rating of yourself in relation to that elite player. Eventually, you will find yourself right "on target."  All the conditioning, practice drills and strategy sessions you engage in will prepare you for some tough competition. But they won't prepare you for the worst-case: injury. The possibility is always there but until it happens to you, it's not something you devote too much time or thought to. Suddenly you find yourself in a very different routine--doctor's visits, possible medical intervention or surgery, physical therapy. Your focus is on physical repair of the injured part, but don't forget there is more to the puzzle. What goes on in your mind when injury strikes needs just as much attention. The mind-body connection is vital when healing in the body needs to take place. The physical healing process following injury works in stages, and with each stage are psychological factors that should be recognized. The outcome of any sport injury rehabilitation (SIR) program is four-fold:

Briefly, consider there are three phases of SIR. Phase 1 begins at the onset of injury. Physically there is pain, swelling. Psychologically there is anxiety about the unknown--what did I hurt? How bad it it? Can we fix it? What needs to be done? Will I ever play again? Also you may feel a lot of negativity--responsibility or guilt for "letting it happen." "If I only I had done this instead of that." "I am letting my team down." Phase 2 is the longest phase, both physically and psychologically. It is when the rehab begins. Medical intervention (surgery, cast, brace, etc.) has been done and it is time to get strength and full range of motion back. Psychologically this is a tough time. There is anxiety that the process is taking too long, and motivation to do the necessary exercises decreases. There may be more negative self-talk. "I'm never going to feel better!" By the time Phase 3 arrives you are ready to actually practice sport-specific skills. You may return to play in a limited capacity, eventually fully able to play. In this phase, the anxiety takes the form of a lack of confidence, fear the injury may recur. Fear you may not play up to the level you were before. You may find yourself replaying the injury over and over in your head. You may be hesitant, tentative and possibly strain something else in your efforts to keep your newly mended part safe. Consider Washington Capitals forward Brooks Laich, who, after sitting out a frustrating season mending a groin injury, returned to the ice and promptly "tweaked" the other hip flexor. Likely he was a little hesitant and perhaps overcompensated, resulting in a new injury. You can see how the mind can throw obstacles in your path to full healthy recovery. The good news, however, is that if you pay attention, you can make your mind work for you, not against you. Go back to Phase 1. The anxiety and negativity exists because suddenly you are in a situation you are unfamiliar with, not in control of. You need to take control back, to educate yourself about exactly what happened. Work with your trainer/doctor/physical therapist. Ask lots of questions. Have them show you pictures of the injured area. See what yours looks like now, and what a healthy one should look like. Learn why they are choosing a particular course of action. Understand how and why their interventions work, each step of the way. This is not the time to be passive in your treatment. During Phase 2, it is vital that you stay motivated. The number one proven effective method for sustaining motivation is goal-setting. Either with your practitioner, coach, or on your own, set goals for your progress and ultimate return to play. Washington Redskins quarterback Robert Griffin III, when beginning his long road back from a knee injury, changed the passcode on his phone to the date of the first game of the next season, when he fully expected to be able to participate. Set long-term and short-term goals. Whenever you are feeling down or discouraged, engage in positive self-talk. Tell yourself you are constantly progressing. Make sure you have a support system of family, friends, coaches, and go to them for encouragement as often as you need. Imagine yourself strong and healthy again. If you are feeling isolated from the rest of the team, do what you can to stay part of the group. Attend practices whenever you can, even just to watch. Attend meetings or social gatherings. The point is to stay engaged. Once Phase 3 arrives, see yourself being successful. If (and when) the replay of your injury seems on endless loop, stop yourself and replace it. Make a new "highlight film" in your mind. One where you escape injury, make the right moves, emerge unscathed and victorious. Make a point of repeating this film over and over. SIR is never a one-size-fits-all process. There are often setbacks, curve balls. But if you can stay mentally strong and in control, you can handle anything. You will actually come out on the other side even stronger and more confident than you have ever been. Knowing that the possibility of injury is part of any sports endeavor doesn't have to keep you from fully performing. With a strong mind, you will defeat injury; it will not defeat you. Upcoming Articles:

Female athletes are disciplined, determined, tough and competitive. They face challenges head-on, constantly adapt to greater workloads and monitor their gains and performances closely. They are in control. Until a challenge comes in the form of the joyous celebration of pregnancy. Their best traits are encroached upon by new fears, threats to identity, confidence, and difficulties with maintaining high training levels. What is happening? The athlete mom-to-be sometimes gets the feeling, and rightly so, that changes are happening in her body that are beyond her control. Nature is in charge of this phase of development, and this can be scary for someone who is used to being so highly in tune with her body, every movement or sensation. Who Am I? Ask an athlete who she is, and she will probably answer in terms of her sport. "I am a runner." "I am a soccer player." "I am a fitness professional." Her identity and her sport are one. Now she faces a crisis of sorts--"If I can't participate in my sport now while I'm pregnant, who am I?" Similar thoughts present when an athlete is injured and unable to work out with the team or at the level she is used to. Will I Ever Play Again? With all the changes her body is experiencing, and her need to slow down looming, the athlete inevitably starts to think, "Will I ever be able to compete at my highest level again?" For many, this 9-month period is the first time they have taken time off from heavy training in years, or ever! Having been taught that she must keep training, keep pushing in order to make gains in performance, the forced slow down can wreak havoc with confidence. The fear that every athlete who isn't pregnant will surpass her is a constant gnawing thought. She fears she will be left behind and never catch up. Slow Down?? Safety is absolutely paramount at this time for both athlete and baby. As per ACOG recommendations, exercise is important for optimum benefit. However, there are limitations to activity choices and intensity. The athlete mom-to-be can feel very limited in how she can train, and may think it is worthless to even try since the level is so low. Good News There is good news. The best, of course, is that at the end of this journey, this relative blip in time, a Mom is born! A whole new adventure awaits. The better news is, the athlete reemerges with renewed vigor and confidence, having faced the greatest physical challenge nature can provide her. The key to this result is preparation, planning and focus on the positive during the pregnancy. Do Your Research Find out what is happening as the baby develops and grows. Understand your limitations and why they exist. Find other athletes who have experienced pregnancy. Ask lots of questions. Read anecdotal evidence of mom athletes who have returned to play another day, seemingly having not missed a beat. Have a Plan There is no better way to maintain a level of control and confidence than to set goals. Set short-term goals for yourself in your training. Consider your limitations and plan accordingly. For example, a runner used to 50-mile weeks may set a more reasonable goal of fewer miles or slower speed. This time can also be a great opportunity for cross-training. The body responds enthusiastically to new challenges, and even at a low intensity, a new or different activity can be a big boost both physically and mentally. Thinking ahead, too, planning for how you can work out when baby is here, can reduce anxiety as well. Remember Who You Are This is important: You are more than your sport. consider other aspects of your life, your personality, your activities. It is not necessary to remove yourself from the sport you identify with; to the contrary, if it makes you feel better, stay involved in some way. If you are on a team, find another way to contribute. Continue to attend practices, albeit on the sidelines. Offer a new perspective now that you have one as a spectator. Staying involved can help you feel less like you are being left behind. See What You Will Be Throughout your pregnancy, maintain your focus on your long-term goals, be it a certain level of fitness, competition or successful performance. Use imagery and visualization to see yourself where you want to be. See yourself crossing the finish line, scoring the winning basket, on the medal stand with shiny gold hanging around your neck. See it, and you can achieve it.

The challenges for the female athlete during pregnancy are many, but are not insurmountable. Remember, you are tough, disciplined and in great condition. Your body is up to the challenge and so are you. The sacrifices you make are ones you will never regret. It's not hard to get motivated and to "bring it" for a competition. The excitement, the anticipation, the spectators, the opportunities to shine, they're all there if you just show up.

But what level of excitement, focus or intensity do you bring to practices? Are you there to play or just going through the motions? Basketball great Shaquille O'Neal once said, "Excellence is not a singular act; it's a habit." How do you develop the habit of excellence? By repeatedly doing your best over and over. Practicing excellence. You can't practice excellence if you don't "bring it" to each and every practice. Without the fans, the excitement of competition, the game-time pressure, it sometimes feels like there is no reason to really push yourself, to bring all you've got. But if you practice consistently at lower levels of intensity, this will become your habit. It will be very difficult to "unlearn" this when game time comes. Consider, too, that in many sports there are a number of players vying for the top spots, starting positions. If you give it everything you've got in practice, your efforts will be noticed. If many players consider practices a no-pressure, more relaxed time to just go through the motions of skills and conditioning, those players who contribute more, exert greater effort and practice with more intensity will stand out. To be clear, intensity of effort does not just refer to physical effort, but commitment and focus as well. So how do you know what level of intensity is best? Should you always be bouncing off the walls, all over the place? Relaxed but sharply focused? Somewhere in between? The simple answer is, it depends. On the particular demands of the sport, but more importantly, on you. The ideal level of intensity for your sport is the level at which you perform your best. It is when you can be focused, attentive, make appropriate decisions and act quickly and decisively. When your physical play is intense enough to perform skills at a high level, with control and without any unnecessary muscle tension. When your movements have purpose. So what can you do to achieve and maintain this optimum level? First you need to find it for yourself. Consider a scale from 1-10, where 1 is very low intensity, little to no excitement or activity, less focus and attention, and 10 is ultra high intensity, high emotion, hyper-focused, very physical and driven. Think about the number at which your intensity brings your best performance. It is not always higher intensity that is better. Sometimes a 10 might involve so much emotion or physicality that some control and focus are lost. That being said, some individuals actually perform better at a 10. Some do better at very low intensity, because their sport may involve more thinking, less physicality or emotion. Perhaps lower levels enable them to focus better and make better decisions. The best way to know what level works for you is trial and error. Keep a journal or log of your practices. Record the level you feel describes where you are at the beginning of practice. After practice, record any changes in level you may have experienced during practice. Note how well you played at each level, or if you noticed your playing suffered. Over the course of several practices you should start to see a pattern, a link between a level of intensity and your best performances in practice. You've found your number. Now that you know your ideal number, the trick is to bring yourself to that level in every practice, and keep it there. This can be done in a variety of ways. Cue words, phrases, images or movements are all useful for bringing yourself to the desired level and maintaining that level. Washington Capitals hockey goalie Braden Holtby uses physical movement in the crease in his warmup and at some points during his performance to get in the right frame of mind, to attain his number. During the practice or game he regains focus as necessary by squirting some water from his water bottle into the air and focusing on each drop as it falls. You can adopt similar tactics which, when practiced often, can instantly reframe your mind and bring your intensity to your desired level. Maybe you do some physical movement, high-stepping, swinging your arms briefly, squatting or quick feet. Maybe you bring to mind an image--you see yourself repeating a play you made previously that was appropriately intense and successful. You don't even have to imagine yourself. Say you want to bring explosive movement to your performance, for example. You can imagine a cheetah sprinting after its prey. A fighter jet screaming across the sky. You can also come up with quick phrases that will bring your attention to the desired behavior. "Let's get intense!" "Go, go, go!" "Fast!" "See it!" The phrase is entirely your own, whatever motivates you to reach the level of intensity and performance you desire. Seem like a lot of work for practices? Not really. With repeated use, these techniques will become second-nature. You will be able to bring consistent high-performance intensity to each and every practice. And what will happen? It will become habit. Remember, excellence is a habit. Inevitably what you bring to practice will be there in competition. You will be in control and you will experience success. Count on it. You've just completed the "BIG RACE." So what now? The next race isn't for another few weeks. Back to training. But how can you stay motivated, maintain that sense of self- confidence you had before the last race? A systematic program of setting goals and working toward achieving the goals is a highly effective way to maintain self-confidence and increase competence in running. Research and practice alike have consistently shown goal setting to be extremely helpful in the development of both physical and psychological skills.

Among the benefits of setting goals are:

Set short-term, not long-term goals. Long- term goals are really just objectives, something in the future to shoot for, such as competing in an upcoming marathon a few months away. Such an objective alone won't keep you motivated as much as will short-term goals (weekly or even daily). There are too many outside variables that can interfere when the amount of time between the present and the goal is greater. Short-term goals will enable you to check progress and get feedback as to what directions or actions you need to take to stay on track for your long-term objective. Set performance goals, not outcome goals. You have control over your own performance and nothing else. You cannot control the weather on race day, the other competitor's training or performance. To set an outcome goal ("to win the race") is merely to set the stage for feelings of failure if you happen not to win. It does not make sense to evaluate yourself and your achievements on the basis of attaining or not attaining goals over which you did not have complete control. Instead, an appropriate goal would be a particular overall performance time or times on a mile-by-mile basis. Or if you have particular difficulty on sections of a course, hills for example, focus a goal on performance on hills alone. The goal should cover any aspects you can control completely and nothing else. This is the same for competition and training alike. Success should mean you have exceeded your own performance goals, not the performance of other people. Set challenging, not easy goals. Research has shown that if the goals are too easy or too difficult, motivation drops dramatically. Therefore, goals should not be so easy that they can be achieved without additional effort; they should not be so difficult that you have trouble taking them seriously or that you still cannot achieve them after repeated effort. When you cannot reach a goal that is too difficult in the first place, you may feel you are a failure and your self-worth will be threatened. The best way to determine how challenging your goals should be is to use your most recent performances as a baseline, then set a goal slightly above those, an approach termed the "staircase" method. Continue to set small goals as steps on the staircase where the "top step" is a great improvement from the "bottom step." By the time you reach the "top," you will have frequent opportunities to achieve and build self-confidence and motivation. Each step should cover approximately one week of training. If you find it difficult to reach the next step, reconsider the difficulty of the goal, and divide it into smaller steps. Or check to see if you are using an appropriate training strategy. Set realistic, not unrealistic goals. Don't confuse who you are with who you wish to be. Set goals that are realistic enough for you at the present time (with a little training) to achieve. Don't be afraid to modify a goal that proves to be too much for your present skills. Set specific, not general goals. To "do the best you can" is a positive goal, but difficult to achieve or exceed. Why? Well, how do you know exactly what your "best" is? This goal is much too vague, although it is difficult to fail at, for you can always say you did your best. A specific goal is much more effective because it will direct you to a specific criterion by which you measure your success. You will receive a clear expectation of a quantifiable goal and a specific time period or precise event. Take, for example, "I will run the 1500-meter race on Sunday in 3:57." This goal defines a specific time (3:57) by a specific date (Sunday). Goals are not easy to set, as they do take a lot of work on your part. But the rewards you will get, the sense of self-worth and increased motivation will make all your efforts worthwhile, and in the long run improve your performance. Good luck!! Originally written by Christie (Wells) Marshall April 2000 for the Washington Running Report Every athlete knows the risks. They also never really think it will happen to them. After all, that's why there are conditioning programs, strength training, warm-ups, stretching. But then there's a misstep, a big hit, an awkward move. Suddenly life as you know it takes a very strange turn. Beyond the x-rays, the treatment, surgery, and rehabilitation lies one more piece of the puzzle that is not always tended to--what changes are going on in your head.

You may attend practice while you heal, but can no longer participate. How does that make you feel? You see the player who is now filling your shoes and doing very well. What thoughts are going through your mind? When it is time for you to return, are you anxious? Scared? Many athletes experience new fears they never considered. They second guess every movement they make--will this hurt? Will I get hit too hard? Will I be able to play as well as I used to--ever? The ideal time to begin to address all of these is ideally as soon as treatment starts. It's important to be able to talk to someone about your concerns. It is also important to come up with ways to calm your fears. Relaxation to calm your mind, and using mental imagery and visualization to see yourself back in action are effective tools. Another is positive self-talk, reminding yourself of where you were and how far you've come, how strong you still are. Know that your skills, while they may be a bit rusty at first, are still there. They will return. All is not lost. Imagine yourself back in action. Really feel like you are there. Take in sights, sounds, the feel of being back. This may seem obvious but is important to note--when you are imagining, you are completely in control of your success. Always imagine yourself being successful! You perform flawlessly, at the top of your game. You can even visualize a situation similar to what caused your injury. This time, though, you escape injury. You catch yourself, move properly, avoid the hit. Feel your confidence grow with each scenario. These are just a few examples. There are so many techniques you can use. Choose what works best for you. With appropriate mental preparation, you should have very little trouble making your triumphant return. Great news! You don't have to be an Olympic contender to benefit from mental techniques. You don't even have to be in great shape. You just have to want to commit to achieving a personal best in your chosen activity.

Sit down and do an assessment. "Where am I now in terms of this activity, and where to I want to be?" When you have those two answers, you simply connect the dots. What lies along the line between them are your goals. The end point is your ultimate, long-term goal. The ones on the line are shorter-term goals. (See the article posted on Goal-Setting) Now, to achieve each goal, decide what you need to do to get there. Here's where you can apply various mental techniques. A golfer experiencing the "yips," and wishing to eliminate them, can implement relaxation, ritual and visualization to assist in gaining focus and control. If you are new to a sport and learning skills, imagery can go a long way to helping your body lock in appropriate processes and movements. A runner attempting an increase in race mileage, a 10K or even a marathon, can benefit from self-talk during the race, or the use of associative or dissociative techniques to focus on how the body is feeling, or take your mind elsewhere to rhythmic patterns of counting or breathing or the like, respectively. Great gains can be made, goals achieved, motivation maintained, and above all, fun had just by applying tools of sport psychology to your endeavors. |

Articles for Athletes

Information to help you achieve your personal best performance! Archives

February 2016

Categories

All

|